New book distills three decades of learnings on survey design

Despite all the digital and virtual means by which the world is connected, when it comes to a researcher in, say, Brussels trying to get to know a community in, say, Almaty on a level that’s technical, substantial and deep enough to include in research, a physical, vocal or face-to-face survey still yields the best results. (And isn’t that nice?)

So posits UNU-MERIT professorial fellow Anthony Arundel, who began his research into survey design in 1993 and has only been expanding it through multiple digital revolutions since. In his latest book How to Design, Implement, and Analyse a Survey (Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., 2023), Arundel shares his learnings – and general wisdom – in a concise and easy-to-read handbook that efficiently summarizes all he’s absorbed during his tenure journeying deep into the art of gathering true answers. Here in this interview he shares a few highlights.

The book can be purchased in print or downloaded for free from the Edward Elgar website.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

How long did it take you to master the art of carrying out a survey properly, from start to finish?

Survey methods are never fully mastered because new methods and technologies continually change the options. For instance, in the 1990s we could send a survey out by fax. This is no longer possible, but now online surveys and web testing are possible. In the last five years, smartphones have added a new way for people to reply to a survey, creating new challenges for survey design.

How should you choose between conducting a survey physically, digitally or via audio or phone?

There are multiple factors to consider, such as the types of questions you want to ask, the characteristics of your target population and how fast you need results. Matrix or grid questions are difficult to ask in a telephone interview and almost impossible to ask if people answer on a smartphone, but simple to ask in a printed questionnaire sent by post. Some populations can only be reached in a face-to-face survey, while telephone surveys provide the fastest results.

However, for most surveys there are two dominant factors: cost and the goal of getting the highest response rate possible. Online surveys are the cheapest, but they have substantially lower response rates than other survey methods, such as a printed questionnaire sent by post with a pre-paid return envelope, or a telephone survey. A good compromise is to conduct a mixed online/postal survey, which will obtain a higher response rate than an online survey alone and at a moderate cost.

What are the key elements of a well-designed survey?

A survey consists of three main parts: 1) the questionnaire, 2) the method for identifying a sample of individuals, and 3) a protocol or set of rules for delivering the questionnaire to them. The last two are discussed extensively in Chapter 5 of my book and largely require attention to detail and following the protocol.

I would like to focus on the questionnaire, which is the central part of a survey. As explained in Chapters 2 and 3, the first rule for writing the questionnaire is to exclude any questions that you don’t need and not omit any questions that you do need. This rule requires throwing out questions that are “only nice to know” and giving careful thought to what you need for your research. The second rule is that all respondents must understand each question in the same way, and all respondents must be able to give reasonably accurate responses. Meeting this rule requires extensive testing of the questionnaire with individuals that are drawn from your target population. The best testing method is called cognitive testing and is explained in Chapter 4. It is good practice to start testing your questionnaire on friends and colleagues, but this isn’t enough. Questions must be cognitively tested with individuals from your target group, preferably in an interview.

The second goal requires ruthless deletion or revisions to questions, even though you might have spent hours developing them. People find this very difficult to do, but it must be done.

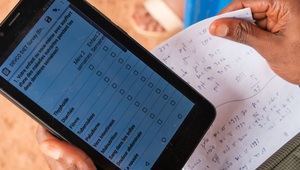

A community health worker conducting a survey in the Korail slum, Bangladesh. Photo: Lucy Milmo/DFID

How long can you expect to spend creating a well-designed survey?

It depends on your level of expertise, but the average questionnaire of six to eight printed pages can take about one or two months to develop, plus another month to test with individuals drawn from the target population, followed by making necessary revisions. It requires about two to three months to identify the population of individuals for a target population, draw a sample, and develop the survey protocol. These steps are followed by another two to three months to implement a survey. If you have sufficient staff, the population identification and sampling can occur at the same time as developing the questionnaire. Chapter 2 provides a time budget of six months from the start of questionnaire development to the end of data collection, but this is for a well-resourced survey by experienced individuals.

People who have no survey experience are almost always shocked to find out that it takes this long – and realistically even longer – particularly for developing and testing the questionnaire. But the questions are very important. If they don’t obtain good information to answer research questions, the entire exercise can be a waste of time. Testing is vital. I have a lot of experience with writing survey questions, but up to half of them can fail a first round of cognitive testing, requiring revisions and a second round of cognitive testing. Some questions never succeed and need to be deleted.

What can be done to get a good response rate?

High-quality data (dependent on a good questionnaire, sample and protocol) and a high response rate are two of the most important goals for a survey. Chapters 1 to 5 of the book describe multiple methods for improving the response rate, but these can be grouped into three methods: a short, easy-to-read questionnaire that is also, importantly, of high interest to the respondents; personalization of the survey delivery so that it does not look like a mass mailout or spam if online, and a good follow-up protocol for reminding non-respondents to answer. Personalization is often time consuming but worth it. For instance, potential respondents to an online survey should first be contacted through a letter sent by post instead of by email. Mailed correspondence, if time allows, should include a handwritten address on the envelope and a real stamp.

How can you know if you have asked a good question that will produce true and accurate answers?

Questions need to be simple and only contain one question. People frequently get this wrong, often not realizing that they have written a question that contains two or even three separate questions within it.

Even the best efforts, however, can miss problems with a question. This is why I always recommend that people include questions for alternative dependent variables if they plan to use survey data for regression analysis.

How can you tell if you are getting inaccurate or untrue answers?

It is not always possible to determine if an individual response is accurate. For this reason, it is good to have a reasonably large sample so that inaccurate responses do not dominate the results. You must always be prepared for some statistical noise in a sample. But, in addition to cognitive testing, the quality of the results can be improved through a process of ‘data cleaning’ and analysis, explained in Chapter 6. Data cleaning checks all responses for logical inconsistencies, such as conflicts in the responses to two or more questions, and for missing data. For some responses, you might need to contact the respondent to check that an answer is correct.

No matter how carefully and lovingly you have designed and tested your questionnaire, some respondents will misunderstand one or more questions while others will get bored, particularly if the questionnaire is too long, and race through the remaining questions without paying much attention.

Nutrition survey being carried out in the village of Bafwaboli, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Photo: Axel Fassio/CIFOR

What are some of the most common survey mistakes you see among researchers?

All researchers, both early-career researchers and the more experienced, write questionnaires that are far too long and far too difficult. This is even after they have been admonished to keep their questionnaire short and simple. They often don’t realize that the words that they use all the time are impenetrable jargon to others. Or they think that everyone will take the time to carefully read a demanding and complex question. Since people read survey questions quickly, they need to be written in a language that is much simpler than the respondents’ level of education. For example, questionnaires sent to highly educated business managers should use language that high school graduates would understand.

The second common survey mistake is to cut corners, usually due to running out of time or an inadequate budget. It is important to never skip cognitive testing, never send questionnaires to an unnamed individual such as to “the resident,” “the CEO” or “Human Resource Manager” and never skip on a good follow-up routine for non-respondents.

What is the best survey you have ever designed and/or taken, and why?

It is difficult to identify the best survey I have ever designed, since they vary a lot in length and purpose. The highest response rates were from one or two-page fax surveys, but sadly those days are long gone. I always answer surveys that people send to me, largely out of professional interest. Some of the surveys I receive are part of an academic study and are simply dreadful. They do serve a useful purpose though, as they are my best source of examples of terribly written questions.

ANY COMMENTS?

NOTA BENE

The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of UNU.

MEDIA CREDITS