From left to right: Karthika Baby Sujatha, Praachi Kumar, Giovanna Mazzeo Ortolani, Elena Camilletti and Paloma Assuncao

Today marks the end of our PhD Research Week and to celebrate the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, this blog post is dedicated to the work of five of our talented female PhD fellows who are all working on topics related to gender and the empowerment of women and girls.

Praachi Kumar

Praachi Kumar is investigating whether new media can challenge gender norms in India.

Background

Son preference (the desire to have sons instead of daughters) in India is a widely known and thoroughly documented phenomenon.

A recent journal article states, “There has been a documented imbalance in India in the sex ratio at birth (SRB; defined as the ratio of male to female births) since the 1970s. The masculinised SRB for India is a direct result of the practice of sex-selective abortions at the national level. However, unlike other countries similarly affected by sex imbalances at birth, India is unique in its regional diversity of SRB trajectories.”

Pre-birth gender determination has been illegal in India since 1994, when the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act was passed in order to try to rebalance the national SRB, meaning that doctors and parents who break this law can face imprisonment.

However, as Praachi explained in her presentation ‘Mind the App: Can New Media Challenge Gender Norms?’ during this year’s PhD Research Week, there are clinics and doctors in India that continue the illegal practice of pre-birth gender determination, and sex-selective abortions are still taking place. Furthermore, Praachi shared with her audience that the neglect and maltreatment of girls in India (especially regarding nutrition, education and healthcare) is well documented in the literature, with some media reporting of infanticide.

All of this leads to stigma – affirming gender inegalitarian norms and values – and to demographic consequences: for example, couples may continue having children until they have their desired number of sons, undercutting governmental family planning efforts. (Incidentally, India was the first country in the world to launch a state-sponsored national programme for family planning in 1952 – and according to the UN’s 2022 Revision of World Population Prospects, India is projected to surpass China as the world’s most populous country in 2023.)

Another troubling aspect of sex selection in recent decades is that since there are far more men than women, particularly in certain regions such as Haryana, some men who are unable to find a woman to marry are paying substantial amounts of money to “import” brides from other Indian states, leading to more problems stemming from cultural and linguistic differences.

What shapes gender norms?

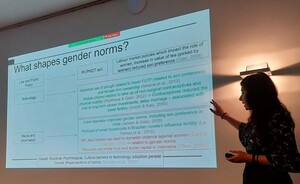

Praachi believes that any conversation about son preference is incomplete without a study of the underlying gender norms and what shapes them. As can be seen in her presentation slide below, during her literature review of the topic, she saw that the following three factors have a strong impact on gender norms:

– Law and public policy

– Technology

– Media and information

Praachi ‘s presentation ‘Mind the App: Can New Media Challenge Gender Norms?’, Wednesday, 8 February 2023

As a result, Praachi became particularly interested in studying the impact of social media on gender norms and decided to make this the focus of her PhD research, using the following question:

How does social media penetration impact gender norms?

To tackle this question, she has taken datasets from three sources and has processed huge amounts of data.

Karthika Baby Sujatha

Karthika Baby Sujatha is examining whether the gender quota introduced in the Indian corporate sector has been successful in increasing women’s effective participation in corporate affairs.

Karthika’s presentation ‘Corporate Board Quotas and Women – Sharing space without sharing power?’, Wednesday 8 February 2023

Background

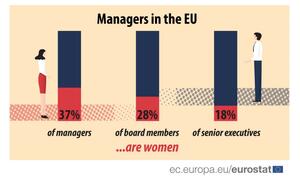

Although there has been significant progress in terms of greater gender equality in the labour market over the last decades, women remain heavily under-represented in high-earning, high-status occupations in the corporate world. For example, despite comprising 46.4% of the total labour force, women account for only 28% of board members of publicly listed companies in the EU, and less than one fifth of senior executives positions (18%) in 2019, according to Eurostat (the statistical office of the European Union, 2020).

The situation in developing countries such as India is unfortunately even worse due to various social, cultural and religious aspects – according to Oxfam’s India Discrimination Report 2022, ‘gender-based discrimination is found to be extremely high in all employment categories in both rural and urban areas of India’.

Thus in order to increase the participation of women in key decision-making roles and inch closer towards gender equality goals, in recent years, the Indian government has begun adopting new policies and laws supporting female empowerment in the workplace. The idea of mandating gender quotas on corporate boards has gained increasing political traction worldwide. Ten years ago, India became the first developing country to have enforced a quota mandating listed companies and public limited liability companies with a minimum paid-up share capital and turnover to have at least one women director on the board, through the revised Companies Act, 2013.

Deloitte Global’s ‘Women in the Boardroom’ 2022 report (image below) revealed that women now hold 17% of the board seats in India, an increase of nearly 10% since 2014 (due in no small part to the 2013 Act, one imagines). However, only 3.6% of board chairpersons are women, showing there is a long way to go.

Effects of gender quotas

Karthika explained during her Research Week presentation ‘Corporate Board Quotas and Women – Sharing space without sharing power?’ that since qualified women might lack the right network to help them climb the corporate ranks, quotas can provide the initial step up that women need. In other words, having a mandatory quota can help women overcome challenges concerning social and institutional factors that often impede their career avenues and growth.

However, Karthika learnt during her review of the literature that gender quotas are not completely free of repercussions. Sometimes, they have led to mere tokenism rather than ensuring women’s active participation on the corporate boards. Those opposing gender quotas argue that there are not enough qualified women for the reserved board seats. Furthermore, certain firms may have decided to play strategically by appointing women with sub-par qualifications to their boards, expecting them to have minimal participation in board decisions – and of course, even if these firms comply with the quota, this wouldn’t necessarily mean the success of the policy.

With these contrasting points of view in mind, Karthika ultimately chose the following research questions to focus on:

Has the gender quota introduced in the Indian corporate sector been successful in increasing women’s effective participation in corporate affairs? Has it reduced the gender wage gap?

Paloma Assuncao

Paloma Assuncao is researching the economic determinants of gender gaps in child health and education outcomes in south-east Asia.

Background

Gender equality is crucial for development. However, existing gender gaps in income, autonomy, mortality and education show that women still face many disadvantages compared to men. In parts of Asia, these gaps can be even more pronounced, mainly resulting from a cultural and institutional environment that favours men and male kin. In the 1990s, Amartya Sen estimated that 100 million women were missing in East Asia, West Asia and North Africa combined. Subsequent research indicated not only the persistence of excess female mortality, but gender biases are also present among the surviving women, particularly girls in south-eastern Asia. For instance, girls may be more likely to be neglected, with daughters receiving less parental resources, care and education investments in comparison to their male siblings. Despite efforts to mitigate gender biases, the evidence indicates that these biases remain present in the region and may affect child outcomes crucial for their future physical and cognitive development.

An important underlying factor of gender biases among children is son preference, which can be rooted in sociocultural and economic determinants, such as the rigidity of patriarchal kinship systems and the gender differences in the economic returns of children, respectively. However, despite the growing evidence supporting the economically-driven motives for son preference, their relevance may be perceived as conditional on the sociocultural context. Hence, it remains to be better understood how relevant these economic determinants are to gender biases among children. The answer to this question can provide potential tools to policymakers for tackling the adverse consequences of son preference in parts of Asia.

(NB: this section was drafted in consultation with the researcher)Economic returns from children and pro-male biases

With her research, Paloma has been working to understand better what is known about the relationship between the economic returns from children and the pro-male biases in child development in south-east Asia. The paper she’s working on examines the evidence of the impact of gender differences in economic returns on child outcomes. In particular, her research focuses on gender differences in health and education outcomes, as these are most important for children’s development and success in later life. The economic returns under consideration are those arising from marriage transfers, old-age support, labour returns and inheritance rights. Since these returns may differ between sons and daughters, they may help explain the existence of gender gaps in child outcomes. She chose to focus on these returns because they have usually been indicated as potential economic determinants of son preference in patriarchal societies in Southeast Asia.

Elena Camilletti

Elena Camilletti (a part-time PhD fellow) is exploring the topic of unpaid care and domestic work among children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries; a main focus of her research is on the differences by gender in the nature, causes and consequences of such work for children and adolescents in these contexts.

Elena’s presentation ‘The effects of unpaid care and domestic work on education’, Tuesday 7 February 2023

Background

The Sustainable Development Goal 8.7 calls for ending child labour in all its forms by 2025. According to the latest 2020 figures from UNICEF and ILO, 160 million children are estimated to be engaged in child labour globally. However, these estimates consider only those children that are engaged in paid work or work on the household farm or business, excluding those that carry out unpaid household services (also called household chores, or unpaid care and domestic work), such as taking care of siblings or doing domestic work.

Yet, unpaid care and domestic work is widely prevalent especially in developing countries, with stark gender differences: globally, girls aged 5-14 spend daily around 550 million hours on unpaid care and domestic work, 160 million more than boys (UNICEF in 2016). The Sustainable Development Goal 5.4 acknowledges the need to recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work by women and girls. For example, research has found that when done for an excessive number of hours, unpaid care and domestic work can affect women’s employment and lead to their time poverty.

Effects of unpaid care and domestic work on education

Following the first two papers where she explored the nature and causes of children’s unpaid care and domestic work, including from a gender perspective, and how it differs from other forms of child work, Elena is now investigating the effects of such work on children’s education. The research will help elucidate pathways of impact that can help better design interventions to ameliorate any potential negative effects.

Giovanna Mazzeo Ortolani

Giovanna Mazzeo Ortolani is a first-year part-time PhD fellow. Her research proposal looks at how intrahousehold bargaining power relates to food security in the context of cash and food transfers.

During Giovanna’s presentation ‘Cash vs food transfers: essays on food security & gender equality’ on Thursday 9 February 2023

Background

As exogenous shocks from climate change, conflicts, and infectious diseases disrupt food commodities supply, the consequential rise in food prices reduces households’ real income and purchasing power, especially for low-income households. This has led to existing inequalities of income and of opportunities being exacerbated. For example, gender inequalities in food insecurity have increased in the last three years since the pandemic outbreak. In some contexts, girls and women are disfavoured in the food allocation within the household, causing them to be more food insecure than their male peers. Social protection programmes have mixed effects on gender equality overall, as outcomes are path dependent on local cultural and social norms. Nevertheless, cash transfers can effectively improve women’s role in intrahousehold resource allocation dynamics, ultimately stimulating female participation in the labour market. Finally, evidence also shows that women spend resources differently from men and, in some societies, they prefer to receive in-kind food transfers instead, which they are more likely to control than cash.

Cash transfers vs food transfers

As a result of her primary research, Giovanna has chosen the following as the overarching research question of her dissertation:

What is the relative effectiveness of cash versus food transfers in improving gender attitudes and stimulating women’s empowerment in the context of food insecurity in low-income households?

Here at UNU-MERIT, we feel that it’s crucial to have researchers such as these five women working in these fields because they allow us to achieve our mandate of bringing evidence-based research to policymakers and society as a whole. Providing knowledge and awareness around these topics can improve people’s lives – particularly the lives of women and girls.

We look forward to seeing the final results of their work in the coming months and years – as always, any papers that our researchers publish will be shown on our UNU-MERIT ‘Latest Publications’ webpage.

Interested in joining UNU-MERIT’s prestigious PhD programme on Innovation, Governance and Sustainable Development?

You only have 18 days left to apply to our programme if you want to start your PhD in September 2023 (application deadline: 28 February 2023)!

Read more about the exciting full-time and part-time PhD options available to you at our institute here.

For anyone thinking about applying, there are open information sessions happening over Zoom next Monday 13 February at the following times:

14:00 – 15:00 CET (full-time PhD track information)

15:00 – 16:00 CET (part-time PhD track information)

(Please contact the PhD Programme Coordinator, Julia Walczyk, if you would like to register for one of these sessions.)

ANY COMMENTS?

NOTA BENE

The opinions expressed here are the author’s own; they do not necessarily reflect the views of UNU.

MEDIA CREDITS

UN Photo/John Isaac, UN Photo/Jean Pierre Laffont, Maastricht University/H. Pijpers