A post by Alex Hunns, social protection researcher at UNU-MERIT

New UNU research explores the extent to which climate crises affect 20 of the world’s largest refugee settlements

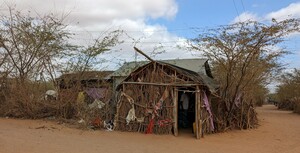

Encampment has defined refugee policy since the Second World War, and refugees fleeing conflict and persecution in their homelands are usually clustered into camps. These camps define a separation or segregation from host populations: physically, camps are located in isolated areas on low-quality land (often with movement restrictions imposed), while refugees are often isolated from national policy frameworks under the responsibility of UNHCR (the UN Refugee Agency). Camps are established as temporary solutions at the sites of fissures between nation states, but this temporariness means camps are rarely established on sustainability principles.

Kenya’s arid and unforgiving north and north-east are host to some of the biggest refugee camps in the world. In the west, Kakuma and Kalobeyei house approximately 250,000 refugees while in the east, Dadaab shelters nearly 300,000 in the Hagadera, Dagahaley and Ifo camps. In situ since the early 1990s after the outbreak of civil war in neighbouring Somalia, Ethiopia, Uganda and Rwanda, temporary shelter has morphed into permanence – with new generations born into the camps – and although communities are sheltered from conflict in their homelands, they face a familiar foe – the harsh and changing climate. Drought has gripped the Horn of Africa – including Kenya’s arid and semi-arid lands in the north-east – for years, destroying lives and livelihoods.

During recent evaluation work for the World Food Programme in Kenya, I witnessed first-hand the strain the drought has placed on refugees in the Dadaab refugee camp in late 2022 and the constant struggle of humanitarian actors to respond to a rapidly changing situation. Born out of this personal experience working in camps in Kenya, as well as Rwanda and Burundi, my collaborators Sonja Fransen, Anja Werntges, Mikhail Sirenko, Tina Comes and I set about developing a strand of research, exploring the extent to which climate hazards and forced displacement interact now, and may interact in the future, to create significant development challenges. This research ultimately led to us publishing an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) journal, which systematically explores the extent to which the world’s 20 largest refugee camps expose dwellers in these impermanent metropolises to slow and rapid onset climate hazards.

Conclusions so far

Our analysis of climate data, using both descriptive and analytic techniques, shows that residents of refugee camps are exposed to slow onset climate hazards – for example temperature and rainfall – at a greater rate than other populations in their host countries.

Refugees residing in Kenya, Rwanda, Ethiopia and Uganda are exposed to significantly higher temperatures compared to their host countries – with the length of time over which extremely high temperatures are observed increasing. Simultaneously, camps in these countries are exposed to lower-than-average rainfall when compared to their host country averages. High precipitation levels, such as those found in Bangladesh, can be harmful.

Though data show that many areas of Bangladesh were exposed to extreme rainfall, residents of Cox’s Bazar – one of the world’s largest refugee camps – face specific risks due to inadequate shelter, while limited water management resources may lead to increases in health risks associated with stagnant water.

Camps in Pakistan and Jordan were exposed, conversely, to lower-than-average temperatures. In Pakistan, refugee camps are clustered mostly in mountain areas, exposing refugees to harsh winter conditions, while in Jordan, the Zataari camp is on an arid steppe featuring hot summers and cold winters. Refugees in camps in Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia and Rwanda are in much hotter and more arid conditions than on average, creating challenging circumstances for life and livelihoods.

With current encampment policies, residents of camps may face unique spatial and socio-economic, cultural and political vulnerabilities, fragile infrastructure, aid dependence, and inadequate shelter, which all interact with climate hazards to produce a significant risk of harm as well as development challenges.

Boda boda touting for business at the exit of the Dagahaley refugee camp food distribution point (Kenya). Refugees can be required to carry upwards of 50kg of home. Credit: Alex Hunns

Next steps

Understanding exposure to climate hazards is of critical importance as policy debates continue on how best to adapt to climate change, which is threatening and will continue to threaten parts of the world hosting large refugee populations. Our forthcoming work will take up this baton of research.

The next research paper – expected to be released this year – is a systematic scoping review, which will highlight the patchwork nature of current research on forced displacement exposure and vulnerability to climate hazards, and will emphasise the need for forced-displacement specific research on the exposure-vulnerability nexus. A following paper will conceptualise the specific vulnerabilities of encamped refugee populations to enable evaluation of the extent to which current refugee policies account for vulnerability.

The research article ‘Refugee Settlements are highly exposed to extreme weather conditions’ was published on 6 June 2023 by PNAS and written by Sonja Fransen, Anja Werntges, Alexander Hunns, Mikhail Sirenko, and Tina Comes.

ANY COMMENTS?

MEDIA CREDITS

“Refugee camp” by Al Jazeera English is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0