A guest post by Francisco Mango, alumnus of last year’s 2021-22 MPP cohort

Research indicates that subnational actors may play a key role in the fight against the climate crisis

Climate change is perhaps the most critical threat to human development. Despite this, multilateral agreements on carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions – the most likely explanation of climate change – have led to frustrating outcomes. The repeated failures of governments to fully implement 1997’s Kyoto Protocol and 2015’s Paris Agreement, among other measures, led to record global emissions in 2021.[1]

The empty leadership from nation-states to fight climate change contrasts with the rising input of subnational actors to global climate governance. Regional states, cities, businesses, and civil society increasingly form and join transnational climate networks. These networks provide local actors with access to the global flow of resources, knowledge, and rule-setting power to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Examples include the C40, ICLEI, the Global Covenant of Majors, Under2 Coalition, and the Climate Action Network. Matsumoto et al. find more than 100 subnational governments – accounting for one-quarter of global gross domestic product (GDP) – committed to net zero by 2050; in many cases, local ambitions exceed those of central governments.[2]

This new landscape made environmental politics scholars outline the polycentric governance of climate change, one where several independent decision-making centres coexist and interact in competitive and cooperative relations akin to the logic of the division of labour. Importantly, polycentricity differs from multipolarity – which some authors claim lies behind the paralysis of multilateral organisations. The big puzzle in this new literature is whether the division of labour reinforces or undermines “closing the emissions gap”. However, difficulties in collecting or accessing local data and methodological challenges to isolate the causes and effects of local climate policies or even the “size of the gap”, have resulted in limited research on the subnational contribution to global decarbonisation.

New data aiding environmental research

Last year, the OECD) and the European Commission jointly launched the Subnational Climate Finance Hub (watch a short video explainer below). The Hub offers a new database measuring the level of subnational government “climate-significant” spending (investment in climate change adaptation and mitigation) in 30 European countries, Australia, Canada, and Japan. Estimations are based on the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance, which earmarks sectors and areas that most contribute to climate change.[3]

Source: OECD website

This new information will help environmental researchers in the polycentric governance literature to analyse the effect of subnational actions in closing the emissions gap. I wanted to contribute to that goal, so for my MPP thesis I investigated whether subnational climate spending positively influences the development of the circular economy (i.e., recycling and reusing waste as inputs and extending the life cycle of material-intensive goods) in Europe.

Local governments: the key towards a circular economy?

The thesis I propose is that subnational actors are a key driver of the circular economy in Europe. Two premises sustain this argument:

(1) the circular economy demands investments and public goods that subnational actors have comparative advantages to supply – e.g., waste management, secondary markets, urban planning, and population density; and

(2) the circular economy has geographical implications on production networks, shortening them from global to national and national to local – thus disconnecting some of the vital links in current global value chains.

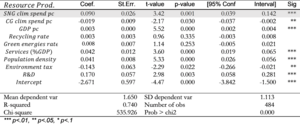

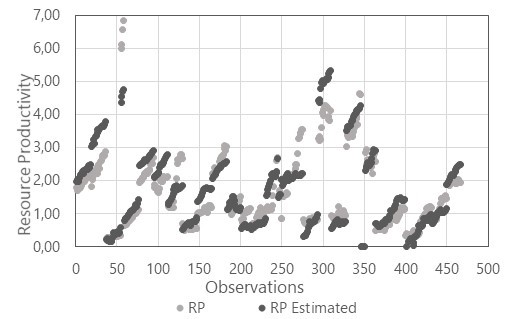

In my research, I use the national demand for raw materials as a proxy of the circular economy. Indeed, resource extraction demand is expected to increase more slowly than production and consumption in a circular economy world, ultimately decoupling GDP growth from natural resource depletion. In light of this, the Circular Economy Monitoring Framework from the EU calculates “resource productivity” as one headline indicator, defined as the GDP divided by domestic primary raw material consumption.

Based on these premises and the available information, my thesis shows a robust positive correlation between climate-significant spending at subnational levels and resource productivity. All things being equal, the more subnational governments spend on mitigating climate change, the less demand for natural resource extraction occurs at the national level. Interestingly, the opposite holds for central governments: the more the latter spends on the same sectors and areas, the higher the demand for primary materials. This is a striking conclusion since the impact of climate spending on the rate of natural resource exhaustion lies in who spends rather than where. I outline the main results of the econometric test in the annex below.

Moving away from centralisation

Despite the reasoning behind the model, the findings are still puzzling since decisions over material inputs demand span many jurisdictions in today’s global production networks. For some authors, sociotechnical system transformations need large-scale, deep, fast, and inclusive policies, making centralization and extensive coordination the (apparent) most efficient supply. Instead, bottom-up, uncoordinated, and localized climate policies have been driving Europe’s low-resource demand circular economies. This encourages us to move from the if to the why question in further research.

Nevertheless, there is more that we can do. According to my model, subnational governments have not increased the “effectiveness” of €1 spent over time. The impact on natural resource demand is the same today as 20 years ago. Most probably, this is due to restricted legal authority to access external funding, enforce policies, and influence Nationally Determined Contributions in the Paris Agreement’s framework.

To conclude, if the findings of my research are consistent across other studies or when replicated using other indicators for subnational climate actions or environmental outcomes, then there might be good reasons to consider a shift in policymaking: moving away from centralisation and instead empowering local governments to achieve a faster and more just transition.

About the author

Francisco Mango is an expert on developmental policy with a long consulting experience in the private and public sectors. His research focus is multilateral governance, economic integration, and international trade. He has worked as a policy advisor and international trade negotiator at the Argentinian government, where he actively contributed with policy experts from the IADB, World Bank, and OECD. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Economics, a Master’s in International Relations, and an MSc in Public Policy and Human Development from UNU-MERIT. Currently, Francisco is pursuing a PhD at the University of Bristol, UK.

REFERENCES AND ANNEX

[1] UNEP (2022). The closing window. Climate crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies. Emissions Gap Report.

[2] Matsumoto, T., D. Allain-Dupré, J. Crook, and A. Robert (2019). An integrated approach to the Paris Climate Agreement: The role of regions and cities. OECD Regional Development Working Papers, 2019/13.

[3] OECD (2022). “Subnational government climate expenditure and revenue tracking in OECD and EU Countries”. OECD Regional Development Papers, No. 32. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Annex: Panel Data estimations

Panel-Corrected Standard Errors test

Panel data: 30 European countries, 20 years (2001-2019)ANY COMMENTS?

NOTA BENE

The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of UNU.

MEDIA CREDITS

Video: OECD; Photos by Chris LeBoutillier on Unsplash and H. Pijpers / UNU-MERIT | Maastricht University