Meet the new UNU-MERIT board member Behnam Taebi

As a child, Behnam Taebi was interested in nothing more than understanding how everything works, making his education and training as a material science engineer an obvious professional choice.

Now, however, Taebi works as a leading ethicist and philosopher in the fields of climate change and energy, developing ethical frameworks from which to address the trials and tribulations of our times. From serving as a researcher and professor at Delft University of Technology to advising policy through the TU Delft Initiative as well as the recently established Dutch Scientific Climate Council, all the while continuing to author numerous academic papers and books, it’s clear he’s captured an unobvious yet societally necessary niche.

To Taebi, the links between his past, present and the global future are obvious. “My solid foundation as an engineer is something that I’m still using in my work as a philosopher, because philosophical reflections need to take into account the states of engineering,” he says. Here, as a newly appointed member of the UNU-MERIT International Advisory board, he shares more about his unusual path and what it means.

How do you define ethics, and how did you come to make them the focus of your work?

Ethics is systematic review of what is right and wrong. I’m interested in this because I think there are a lot of right-and-wrong questions in technological developments, but very often they remain implicit. I try to make them explicit.

When I graduated as an engineer, I moved toward philosophy, motivated by being particularly annoyed with public debates and how certain issues were being discussed. When it came to sophisticated pieces of technological development or engineering like nuclear energy, they were very often given binary assessments – yes or no – and I was always interested in knowing more. Are you saying no to any possible nuclear technology in the future? Or if you say yes, would you categorically endorse all sorts of nuclear technology, regardless of risks involved?

I started there, and then a couple of years later, I defended my dissertation on justice between generations and nuclear energy production.

What advice do you have for young researchers or academics working on such divisive topics with strong debates around them?

I think with these kind of topics, some level of controversies are unavoidable, and that’s not always a bad thing. I think they say a lot about the societal stakes. But what I try to do is stay outside the political, binary debates. I don’t have a stance for or against nuclear energy. I do have a stance on what I think should be the language for discussing their future. We philosophers hope to provide a vocabulary for such debates.

To make it less abstract, I like to think in terms of public values. We want nuclear energy because we want to provide supplies certainty or the continuation of energy resources. But of course, there are other values at stake such as safety, ecological issues, economic issues. So it’s about balancing these values, and that’s where ethics are involved; if you only focus on the yes and no, these values and value conflicts remain unaddressed and hidden.

What does being an engineer mean to you?

A lot of grand challenges of the 21st century strongly depend on engineering, but some people consider engineering in isolation, sometimes even as a techno fix. We see a problem, and then we put an engineering band-aid on it. The societal reality is often much more complex, and engineering is embedded in society. So, new developments have new implications, and sometimes might create new problems. Currently, we approach a lot of engineering developments in reactive mode. We develop something, put it on the market, things go wrong, and then we start responding to it.

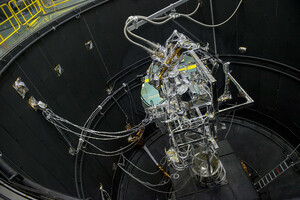

Satellite test set-up inside ESA’s vast Large Space Simulator chamber. Credit: ESA-G.

I like to promote being a proactive engineer. Engineers determine a lot of the world’s future. But engineers need to address certain societal and ethical issues prior to development rather than as a response to something that goes wrong.

Take justice, a notion that I’m interested in from different perspectives, such as the justice of energy production and climate change. But what justice entails is something that needs a conceptual clarification. What many philosophers are trying to do is put more flesh on the bones (sorry! I know that’s not a very vegan expression) and add more substance to the discussions on what fairness and justice mean, because different meanings can lead to different types of design and development.

Are there certain philosophers or schools of philosophical thought that have shaped you and your work most, either directly or indirectly?

I’m particularly indebted to recent contemporary philosophers who started talking about climate ethics. People like Stephen Gardiner have have been very important in my thinking and the way I position my own work as a climate ethicist, but one that is aware of the state-of-the-art of engineering.

Why are you focusing on climate and energy ethics now?

I think climate change is one of the biggest – if not the biggest – challenge that we will be facing in the coming century. It has already started, and it will exacerbate over the next decades. It will challenge where we stand as a society. It will push us to rethink and redevelop a lot of things. It will potentially cause a lot of trouble.

And it’s important to be ahead of these developments as much as possible. We need to not be acting only in the responsive fashion or in the techno fix fashion. It is important to think about the options for the future of energy system, the future of infrastructure. The future of mobility, the extent of our dependency on fossil fuels. These are questions that you cannot answer without a profound understanding of engineering.

You have said that you guard against techno optimism. Could you expand on this?

I would certainly not consider myself a techno pessimist.. There is a lot of literature in which many people consider engineering only as something that has caused a problem, such as that climate change comes only from the time of the Industrial Revolution and other technological developments. Yet we shouldn’t forget how much progress we’ve made in other fields, such as in health and mobility, and we have the same developments to thank.

In the book Under a White Sky by Elizabeth Kolbert, she reviews different technological solutions for climate change, showing how when you bring in one, it could lead to unknown implications that make you bring in another, and so on.

I do believe in engineering. I do believe that technological developments could help us solve a lot of challenges of the current century – but we shouldn’t fixate on engineering solutions per se. Sometimes there are things that we should just refrain from doing, and sometimes behaviour change is what we should look for rather than engineering solutions. So I’m very much interested in fine-grained ethical analyses of needed and feasible technological developments.

You’re an ethicist, a philosopher, an engineer, a climate expert. UNU-MERIT as an institution also has a broad repertoire of areas of expertise. In today’s world, do you think it’s better to be more interdisciplinary or develop a deeper, narrow focus?

I don’t think it’s an either-or, honestly. I’m a big fan of interdisciplinary work because I think a lot of societal challenges can only be addressed in an interdisciplinary fashion. You cannot talk about migration from only one perspective, for example. However, in many instances, it’s important to also continue disciplines as they are, such as that we will always need chemical engineers.

But the future chemical engineer is the one who needs to also better understand moving away from fossil fuel and what that requires of new materials and new processes, and then what implications those have, in terms of ecology, public health, economy, etc.

So we perhaps need to educate our future generations in a different way. And that could be partially in a strongly interdisciplinary fashion, but partially kept within disciplines. We will certainly remain dependent on both.

ANY COMMENTS?

MEDIA CREDITS

Photos by Patrick Post; Nicolas HIPPERT on Unsplash; CTAO and ESA-G on Flickr